Vienna is now one of my favorite cities in the world. Definitely a Top 3 European city for me.

On my first visit, twelve years ago, I thought it was nice, but so much more stood out to me when I spent some time there this summer. The ease of getting around to different places, the green spaces within the city, and the liveliness of the people. Not to mention all the beautiful alpen locations a short distance outside of town. I truly felt a little jealous of the people who got to permanently call Vienna home.

This feeling was validated by the city ranking number one in the world for “livability.” I decided to take a deeper look at what makes Vienna such an ideal place to live, and learned quite a bit about the city: particularly its unique public housing model. The Viennese have it pretty good.

Vienna: The World's Most Livable City

When you’re just a tourist somewhere, it’s easy to keep your eyes peeled for the big famous sights while overlooking the simple things that simply make a city a great place to live.

Things like accessible housing prices, reliable infrastructure, or great pedestrian friendly spaces to go for a walk.

But I got to visit Vienna fresh on the heels of it being named the most livable city in the world.

What makes a city so livable? According to the Economist Intelligence Unit, it’s stability, healthcare, education, infrastructure, culture and environment.

So I kept my eyes peeled for these things.

People living in Vienna indeed have it good. While there, I kept thinking about how neat it would be to raise kids somewhere with strong education, walkable streets, and proximity to the alps. Make a city kid-friendly and odds are, you’ll have made a city that works well for everyone.

I also like what my friend Habib in Sweden once said to me: “I want to live in a city with soul!” His favorite city was Beirut, by the way.

Only Wonder Comprehends Anything

I love those words by St. Gregory of Nyssa: Only Wonder Comprehends Anything

Our world has felt pretty unstable these past few years, and I think a lot of that is related to how quickly things are changing. These changes are very visible, and change always brings along uncertainty.

Uncertainty makes us uncomfortable. From an evolutionary perspective, unknown things threaten our survival. People respond to uncertainty all kinds of ways, many of which are unhealthy. This is probably why St. Gregory’s quote is packaged around him also saying “concepts create idols… people kill each other over idols.”

But we’ve got another option.

“Wonder makes us fall to our knees.”

Stoke wonder. Feed curiosity. Keep that alive in yourself. Feed it in others.

Prep for a Storytelling Trip with Me

Get ready for a storytelling trip with me. These are wild!

Here’s the most paradoxical thing about them:

You want to do as much planning as possible. Have a sense of what question you’re trying to answer beforehand. Do a little research to see how others have gone about it. Map out the places you want to go and the people you want to meet and all the things you want to learn. Plan the shots, script what you can, and get ready to roll.

Then show up, and be prepared to throw it all away.

Be fully present. Let your experiences inform the story.

Be human and connect with people FIRST, before worrying about recording and all that. Then, y'know, hit record.

You probably won’t throw it *all* away. The scripting and all will have been helpful. But you will most certainly be surprised and have perspectives shift by being there.

Here’s how I gather ideas and get ready for an international storytelling trip.

Development Looks Different Everywhere

This was always going to be complicated, isn’t it?

I was in a village, camera in hand, suddenly surrounded by dozens of children. That morning I had just talked with my team about how to tell stories of people who live in one of the world’s poorest settings without being sensationalistic or exploitative.

That’s not the story we’re here to tell. That’s not the story that really helps anybody, I often repeated.

And yet, the visceral signs of poverty were everywhere. Aged clothing. Kwashiorkor.

And it became more apparent that telling a good story in an ethical way involved so much more than making sure our pictures wouldn’t look like they belonged on an infomercial with Sarah McLaughlin.

Using a magic wand on Photoshop to hide the uncomfortable parts of what I was seeing in person? That can’t be right, either. Especially since many of the people I talked to shared how difficult it was to feed their families and make basic needs. Isn’t avoiding those elements in the name of ethical storytelling simply toxic positivity rebranded?

—-

Driving between the city and the village wasn’t far. Geographically, that is. But the quality of the rugged roads meant that even a short distance would take hours.

Going between the two spots allowed me to see the change in lifestyles as we got further outside of town. On the outskirts, on the sides of hills, were a number of fairly large houses. Perhaps five or six rooms, plus impressive verandas and balconies that overlooked the whole valley. The white stucco exterior and polished tiled floors stood in contrast to the clay brick homes we saw further outside.

It struck me how much these homes and this particular spot in Burundi reminded me of the Philippines. The two probably don’t get compared a whole lot, but the look of these homes and their construction style were so reminiscent of upper-middle class homes in many Filipino cities.

Throughout my lifetime, the Philippines has seen steady economic growth, nearly doubling the annual income per person over 30 years. Burundi, on the other hand, went the other direction, seeing that number halved. This downturn was undoubtedly sustained by the conflict and political instability throughout that window, but as the country appeared more peaceful than it had been in a long while, I wondered if a moment of growth might be on the horizon, and if these houses could be a sign.

Like Burundi, the Philippines has areas where poverty is intensified, and people’s homes are rugged structures made from scrap wood and metal. Like Burundi, there are also cities, middle class homes, and areas of decent infrastructure. The difference between the middle-income country and the lower-income country is in the ratio of people who have access to security, infrastructure, and comfort.

When we think of global inequality, we often think in terms of country comparisons. We’d probably be better off if instead we compared different parts of the same country. We’d see similar patterns in most places. Wealth and jobs tend to concentrate around cities. Poverty is much more pronounced in rural areas.

Lifestyles also tend to be drastically different between urban and rural areas as well. Perhaps this is an obvious statement, since this dynamic applies pretty well to the United States and likely every country.

This became especially apparent to me as we talked to people.

After interviewing a man from one of the villages, we asked to take pictures of him and his wife. When we asked him to pose with his arm around her, they posed with uncomfortable expressions, his elbow resting bent on her shoulder. The final product was an endearing, avant garde-looking photograph, but the process reminded me that things you could take for granted in the city might be considered pretty foreign up here.

—--

A lot of these sights made me think of an image I’ve had stored on my phone for years. One that says ‘There is not a more developed or less developed culture.’

The reality is, I’m an outsider to this sort of poverty. I share the stories that people have told me they want people to know about, while recognizing that it needs to be done with a lot of humility. It’s far too easy to create assumptions based on Western expectations.

One thing I’ve grown more sensitive to is the fact that development or progress will look different in different places.

There isn’t one linear path forward.

Some societies put a greater emphasis on money, measuring success in graphs designed to chart economic growth.

Others place a value on having time, opting to operate at half-speed for weeks, months at a time. After all, life is a precious thing. You’re going to want to savor it.

Other places and peoples will see wealth as more synonymous with family, aesthetics, or natural resources. I remember having an Umpqua dentist tell me he was raised to measure his wealth in terms of what he was able to give away.

So then what? If everyone’s concept of progress or development is a little bit different, how do you move forward? What metrics do you even use?

Ambiguity can easily turn into an invitation to disengage.

‘Huh, good question. Guess that’s not our business as Americans, though!’

But so much of the inequality between different parts of the world are the result of colonialism, conquest, and slavery… things that many of us have benefitted from.

We have some moral responsibility to work against things like poverty and inequality, but we don’t have the authority to be perfect arbiters of our success.

Do we even know what that’s like?

I guess that’s why listening to locals will always be important. Hearing their stories will always be important. Working relationally, not just transactionally, will always be important.

Poverty isn’t a culture. Poverty isn’t a characteristic. It is still something worth working against, and we shouldn’t think of it as a cultural expression.

However, we should be humble enough to realize that progress against poverty may look completely different than what we expect.

—----

I have dinner with a man named Enos and his wife. They live in a pretty remote village, and getting to their home takes a bit of a climb up a hill.

He talks to me about their old life and their new life. Regenerative agriculture and environmental restoration made a big difference in their ability to grow food. They used to eat once a day. They used to skip a lot of meals. Now they eat three meals a day.

Then I look at his kids eating their dinner and I remember that he has five. When he tells me that the family eats three meals a day and never skips, that's 27 meals a day in total. A pretty significant feat.

His village is still rural, his home is remote. But now it has a solar panel. Many of the village kids are still showing kwashiorkor, but the replenished soil lets Enos grow more food. Maybe soon his neighbors?

There was a time where I would have written his village off as poor, and yes, widespread poverty remains. But it also makes progress. And again, the world is complex.

My inner idealist wants every place to solve their problems and make progress in a way that is totally theirs. Self determination is extremely important.

Of course, in our more complex world, cultures, people, and places aren’t insulated from each other, and every act of self-determination is also shaped by a plethora of outside influences. Maybe that self-determined path still takes clues and inspiration from Western sources.

How do you know when a place truly determines its own development? It’s never really that simple and straightforward, is it?

Is Korea an example? It’s now such a major exporter of culture, and many traditions, art styles, dishes, etc. have been passed from one generation to the next. But there’s also a sense of a generation gap, a change in thought from an older generation to a younger one. These evolutions are perhaps natural, and things aren’t better by default just because they’re older or newer.

Progress is a funny concept.

These days, I’m less bothered by the tension. More curious.

Suicide Prevention Month

“Sometimes even to live is an act of courage.”

— Lucius Annaeus Seneca

September is World Suicide Prevention Month.

I’ve long looked at suicide prevention mostly through an individual lens. Checking in on friends. Knowing the signs. But preventing suicide is also a cultural and societal level task that includes:

Normalizing conversations about struggles and mental health.

Being intentional around the language used around suicide. (ie. Avoiding terms like “succeeds” or “fails,” referring to an attempt.)

Creating a world that is safer for young LGBT+ people, who have disproportionately higher suicide rates. Expand services to Indigenous Americans. Native men have the highest rates in the country.

Firearms are the most chosen method for suicide, so enacting stricter gun laws.

Support expanding healthcare access, and making sure mental health care is included.

Supporting crisis services like peer crisis intervention or crisis text lines outside of law enforcement.

We're Wrong About Poverty

Poverty is a complex thing to talk about.

There are so many stereotypes associated with it, so many examples of people depicting poverty in ways that diminish the humanity of people with that experience.

And yet, it’s a reality for so many people and a root cause of so many problems we need to talk about it. So many people have shared with me their challenges while living in poverty because they want other people to know about them. Sensationalizing poverty is not ethical storytelling, but neither is omitting it entirely, or romanticizing it.

You’ve got to be humble about this, because no amount of research or travel can give you the full insight that comes with lived experience.

Remember that poverty isn’t a fixed condition. People, communities, even entire countries have shown us that living with insufficient resources is not an inevitable condition.

Put poverty in its proper context. Pay attention to where issues like climate change or colonialism have created the conditions for poverty or insecurity. Places don’t have widespread poverty just because.

But most of all, don’t lose sight of the human being in the story. Don’t conflate someone’s personhood with their problems.

Our separation is an illusion

Reacting to the biggest climate legislation of my lifetime

At 5:38 in the morning, I’m underneath a mosquito net refreshing my news feed.

I’m in Bujumbura, Burundi, having spent most of the week in remote locations across the country. A country the U.N. had just named the most food insecure nation in the world. The farming families I met completely embodied climate vulnerability.

As rain grew unpredictable and dry seasons grew longer, these hungry communities were about to get even hungrier… if not for some serious environmental healing.

My return to Bujumbura meant a return to decent internet access. I refreshed my feed to see that back home, the U.S. Senate had done it–the most significant piece of legislation to address climate change had advanced.

I’m a climate storyteller, but political advocacy has never been my favorite vehicle. I recognize its importance, but it’s harder to feel empowered when you’re always waiting on lawmakers to finally get it together.

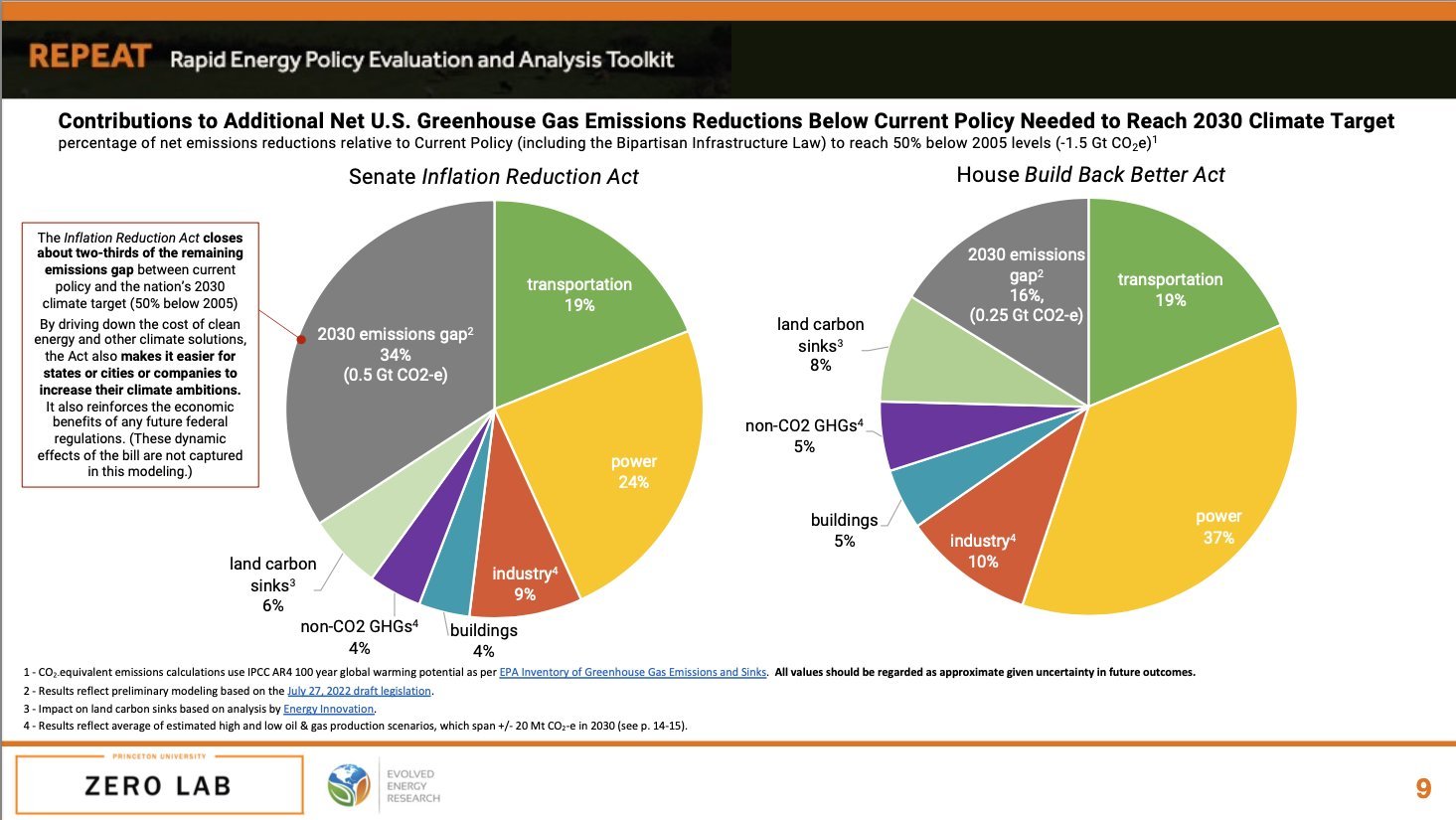

And yet, pulling those political levers is a necessary part of the work. If you do the math, you’ll see that relying on our good behavior as individuals isn’t enough. To mitigate a climate catastrophe, we need that systemic change.

Two weeks ago, it all seemed out of reach.

The narrative was going to be about how close we were to averting crisis, if not for one, maybe two senators. I was feeling a tweet by Hank Green:

In spite of it all, I’ve remained a climate optimist… and I don’t think that comes from a place of naivete. I see the effect climate change is already having on people, like the many I met in Burundi.

But I’ve also seen how emissions have fallen in many countries, how fossil fuels have already peaked and are in decline, and how projections that used to have us charted for 4º of global warming see that number closer to 2.5º– a number that is still way too high, but one that reminds me that we’re capable of moving the needle.

We’re going the right direction, just not at the right speed.

In the U.S., this has happened in spite of the lack of federal policy. In 2009, Congress failed to pass Waxman-Markey, the last big attempt at climate legislation. However, we’ve reduced emissions by even more than that bill was projected to, thanks to state and local action, corporate shifts, and changing social norms.

Because my hope doesn’t really come from the government, it feels weird when it’s occasionally delivered through that vehicle. It’s like watching a scrawny player off the bench hit a game winning home run. Not how I saw it happening, but if it wins us the ballgame…

In short- the combination of policies in this package of legislation set us on a new path. Our previous trajectory saw us reducing emissions by 27% in 2030.

The new number? 42% emissions reductions.

This was the largest investment the U.S. ever made against the climate crisis, a bold win for the planet.

Here’s what I especially like about the bill:

+ Transportation accounts for over a quarter of greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S.- this bill both incentivizes the move towards cleaner vehicles while producing enough energy to meet the demand.

+ It does similar things with greenhouse gas emissions from homes. People will get credits of $7,500 for an EV, $2,000 for a heat pump, 30% the cost of rooftop solar, and $9,000 for home insulation.

+ Most components of the bill both lower emissions as well as living expenses for most people. It reinforces the idea that environmental and financial health support one another. 41% of inflation is driven by fossil fuels.

+ $60 billion is allocated towards environmental justice. This includes $2 billion for farmers who have faced discrimination… largely reparations for Black farmers who have been excluded from USDA loans.

+ $11 billion is going towards restoring and protecting forest and marine ecosystems

+ The bill addresses methane and methane leaks, a short-acting, highly-potent greenhouse gas that probably requires even more urgency than carbon. One of the few changes the bill will create through penalties, rather than incentives.

+ Invests nearly $300 million in sustainable aviation fuel… which can reduce emissions by 50-80%. We’re long overdue for a cleaner way to get around internationally.

And of course, there are some things that could be better:

+ Without investments in e-bikes or public transportation, this plan still maintains our dependence on cars, and doesn’t really advance all the other benefits of walkable cities.

+ Indigenous land sovereignty and management is unaddressed.

+ This bill allows oil and gas exploration from fossil fuel companies.

BUT- for every ton of emissions that are expected from those provisions, the rest of the bill helps avert 24 tons of emissions. And it leaves us with the opportunity to fight against pipelines and pollution generating activities. The bill creates an environment that makes oil leases more expensive and less profitable.

I am unapologetically excited about this bill.

Thanks to the decrease in pollution, it’s estimated to directly prevent nearly 4,000 deaths from respiratory illnesses. It is also likely to create 1.5 million jobs. And it will likely do all this quietly, in the background of our everyday lives, without most of us noticing a shift.

The bill has its flaws and compromises, which will set the stage for future battles to be had. It also leaves more work to be done. The 40% emissions reduction is great, but not enough.

But what I’m excited about is that it renders the work possible.

We’re likely living in the most critical decade for climate action.

What happens now determines whether places like Burundi can continue some of the impressive strides against poverty in my lifetime or plunge into famine. It determines whether or not many of the animals in my kids’ picture books will be extinct by their adulthood, or whether they’ll get to join the efforts for their survival.

And I’d choose that world any day over the one where our generation’s inaction has already rendered their efforts fruitless.

Hours after seeing the bill pass the Senate, we left the city. We went over the Mugere River on a bridge that allowed us to see where children bathed, women washed clothes, and bamboo protected the water source.

Signs of life.

Our separation is an illusion. Decisions made on one side of the globe are often felt on the other.

What happens upstream changes everything. The concept of leaving it better felt so tangible.

I thought of the kids I met here. Then of my own kids back at home. I was eager to reunite with them soon enough. There is more work to be done to leave them with a healthy planet. But now, we get to build off the work that has been done to put that much more within reach.

Jo Koy

I got to see Easter Sunday last week!

It debuted while I was just starting my month of travels and I really hoped I would make it back in time to see it in theatres. I’m in my 30s and this was my first chance to see a Filipino American family on a theatrical screen.

Of course, there are a good number of other Filipino American films. The past couple years have been especially generous, with:

Yellow Rose

The Fabulous Filipino Brothers

Bitter Melon

Empty By Design

But there’s also still a lot of catching up to do. As the second largest Asian American population, with Tagalog being the fourth most spoken language in the US, there are so many more movies to be made and stories to be told!

Global Eats in Toronto

The most multicultural city in the world??

I heard Toronto could make a very good case for the title. Over half its population born outside of Canada. Less segregated than a similarly diverse New York. Very visible examples of multiethnic spaces.

Toronto also happens to be a fantastic food city. Put those things together and it’s basically a giant portal to try nearly any cuisine in the world. You know that had me pretty excited.

With only three full days in town I hoped to try as many different cuisines as possible… but that’s not a lot of time. With limited hours of operation and limited stomach space- I’m pretty proud of what we were able to pull off in such little time.

Burundi Ingoma

It’s finally happening—an adventure that’s been years in the making.

I’ll be visiting a place that’s been on my radar for such a long time, one that nearly happened two years ago.

This one is going to take me to a country full of some pretty tall statistical extremes when it comes to things like hunger and insecurity. This part of the map has been in a lot of headlines this week… and not for especially great reasons.

However, you and I know that those numbers and headlines tell a reductive version of the story and that there’s always a lot more… more that you can’t really start to grasp without some proximity.

It’s harder to reduce people into a simple statistic when you’re up close. And that’s why I’ve been wanting to make this trip happen for years.

In the meantime- I look forward to being more unplugged for the next few weeks. Partly for the really practical reason that internet is no guarantee where I’m heading, but also because I anticipate seeing a lot, having a lot to process, and I definitely don’t want to rush the stories I’ll have to tell.

Plus I’ve spent quite a bit of time in virtual spaces lately, doing planning and strategy and looking ahead at further down the road. Looking forward to more time on actual roads, feet in the dirt, head in the moment to take it in. And you bet I’ll be back with the stories to tell.

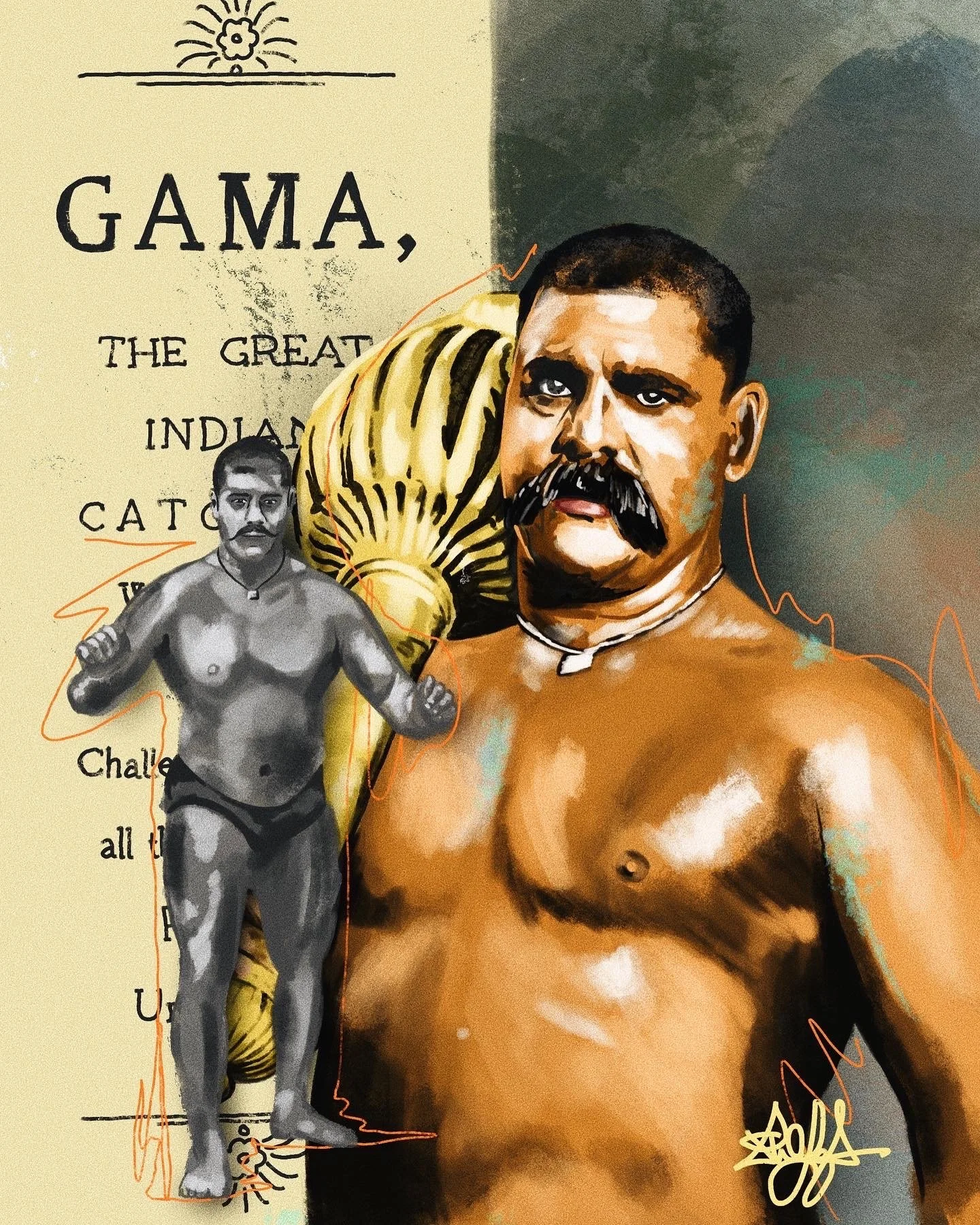

Gama the Great

More like Gama the GOAT. It’s amazing how you can spend a whole lifetime keeping up with something like sports and still only know a sliver of what’s out there.

I only recently learned about The Great Gama. I know it’s always tough sorting out the legends of sports when they go back over a century but this guy could make a pretty good case for being our world’s all time best athlete.

Gama the Great was:

💪🏽 A wrestler from Kashmir

💪🏽 Pro by the age of 10, and India’s heavyweight champ by 1910

💪🏽 An undefeated 5000-0 between 1890 and 1950-something, a whole 60 years

💪🏽 Winner over American wrestler Doc Roller and beat legend Stanislaus Zbysko bad enough to be refused a rematch

💪🏽 A daily consumer of 10 liters of milk and 6 chickens, inspiring Bruce Lee’s diet

Supposedly his greatest feat was preventing a massacre during India’s partition by standing up to an armed group’s leader.

Could you be in a relationship with someone who doesn't like to travel?

A little while ago, I saw a travel blogger I follow post a survey asking if people could be in a relationship with someone who didn’t like to travel. The response was a resounding no, by like 90%.

The funny thing is, that’s kind of one of the biggest differences between Deanna and myself.

And we’ve been making it work for over a decade.

On paper, it looks simple enough. One person can travel, the other can stay. But in real life there’s more to think through. How do we allocate things like money and time off when we’re wired a little differently in that regard? And we do still want to spend as much time together. And with kids in the mix, things are all the more complicated.

It’s probably one of the bigger differences between us two that we have to confront somewhat regularly… and while it’s not always straightforward, it does give us a chance to figure out how to best look out for each other. And I’m still quite satisfied with the amount of travel I’ve been able to do over the past ten years and we both did the memories we have from time abroad.

The Nature of Cities

A little perspective-shift I’ve been chewing on lately.

Most people see cities as the antithesis of nature, as have I. I totally get it. Leaving town and going out into the backcountry for a period of time can change your perspective on things almost upon arrival.

These days, I simply spend a lot more time in town. I have a ton of bookmarks for extended hikes, mountain expeditions, and trails I hope to do someday. At this exact moment, my life doesn’t exactly lend itself to leaving everything behind for a backpack,

But that’s led me towards rethinking how I see cities. What if they’re nature too.

Seems totally counterintuitive at first. But people are a part of nature. And the idea of nature being pristine or uninterrupted by human activity is a Western perspective I too easily assume to be the default. If nobody would debate a complex beehive, spider tunnels, or nests carved into a cove to be examples of nature, why see our built environments too differently?

Of course, all the intensive infrastructure of our cities tends to harm biodiversity in the immediate space, but density tends to be better for big picture ecological health, because it reduces the spread. Then we can look at how stewarding our urban spaces as nature can make them better for people and the planet.

Like things in nature, cities are all about connection and the harmony of all who share a space.

Quetzal

New favorite bird alert… kind of. I can never pick one favorite bird. But let’s talk about the resplendent quetzal for a hot minute.

It’s the national bird of Guatemala- and it’s clear the country loves the quetzal. It’s on their national team’s soccer crest. It’s on their currency… the currency is even named after the bird.

I would love to see the bird while in Guatemala, except the likelihood of that is quite low. They are unfortunately threatened due to habitat loss.

There’s an old story, it’s kind of a legend, of a quetzal that was caught and caged. When inside they decided they would rather hurl themself at the sides of the cage to die rather than to live in captivity. Thus, the quetzal has been a symbol of freedom for so many.

I took my reluctant best friend on a surprise trip

If you ever get the chance to take one of your closest friends on a surprise trip, withholding the destination and coaxing them to come along… go do it.

Especially if it’s to a place as fun as Toronto.

And it’s now one of my favorite cities out there. Such an easy place to get around, so many things to do, surrounded by plenty of nature, and so much cultural diversity.

I’ve shared some bits and pieces already, but here’s the first full cut of all we packed into three really fun days.

Build the Beloved Community

When big things happen in the world, I often react by asking ‘what can I do now?’

One of the worst feelings, in my opinion, is when it feels like there really isn’t an answer.

It’s a feeling that’s gotten a little more common, though, with current streams of social dysfunction feeling like they’re at way too big of a scale for anybody.

There’s the way a culture of bullying has been normalized. The fact that people evade accountability all the time by building themselves a rabid fanbase. And the way the most vulnerable always pay the harshest price.

Of course these problems are too big for any individual. That’s why the way forward must be together.

Belonging is such a powerful need. Sometimes you wonder how so many people seem to live in an alternate reality; in denial about urgent problems while up in arms over fictional ones… but the bulk of our brainpower isn’t meant for logic. It’s meant for survival. And we’ve always found survival in belonging.

People’s ideas and actions are most often determined by their sense of identity and where they find belonging.

It actually makes a lot of sense that our current age of anger comes after an isolating decade, that ended with the UK and Japan appointing Ministers of Loneliness.

There’s a renewed urgency to John Lewis’ charge: to build the beloved community. Not a club that excommunicates members for not being perfectly aligned, but a community where everyone’s wellbeing is interlinked.

Lately, when big things happen in the world, I find myself wanting to be with people. To listen.

It’s easy to feel like the scope of the world’s problems is out of reach… and that’s because it is. But everyone can do something to extend a sense of belonging and I cannot overstate how powerful that is. To know you’re accepted. Not alone.

It’s a game changer for sure.

Japanese Breakfast

I’m watching Japanese Breakfast bring a gong on the SNL stage. What a power move. I’ve been playing Mr. Morale every time I’ve been in the car this week by myself, knowing it’ll take many more spins to unpack everything Kendrick lays out.

I’m reminded of Crying in H Mart and To Pimp a Butterfly and many other favorites. I’m reminded that saying something raw and real as an artist asks for vulnerability- never an easy request.

Cultural clashes have turned so many good artists calloused. It’s replaced vulnerability with viciousness. But I think that’s made real sincerity all the more refreshing when you do see it.

I’m trying to inject more of that into the stuff I create. I simultaneously believe in telling stories from your scars- not your wounds. In other words, some boundaries in between what you experience and how you reflect that in what you create is healthy. But I think it’s easy for me to get too calculated too, which doesn’t give enough breathing room for the whole messy complexity of life sometimes.

Opal Lee

Everybody leaves some kind of legacy but Opal Lee is in a whole other league.

When she was 12, her home was burned down by a mob of white supremacists, catalyzing her commitment to activism.

She spent over 40 years trying to get Juneteenth recognized as a federal holiday, walking 2.5 miles to symbolize the 2.5 years people remained enslaved because they were unaware of their freedom.

In 2016, that became a 1400 mile march to DC. She was 89.

She stayed busy at the community level. In 2019 she launched a farm to combat food inequity in Texas.

Then at 94, her push for Juneteenth recognition came true.

I’m pretty sure that during that 40 year effort, there were many times when it felt like it simply wouldn’t ever happen. Few will have Opal Lee’s experience of seeing a vision held throughout life becoming realized at such a late stage. But few have her level of commitment.

Travel is Different Now

The past few years have made me really rethink my relationship with travel. I still know that I love going places and that’ll probably stick with me for life. But here are some of the bigger shifts:

🏜 Going at as slow of a pace as possible. This is especially important now that I have kids and want to travel with them as much as I can manage. Slow travel tends to be more sustainable, intimate, and it just teaches you way more.

🏔 Trying to go as sustainably as possible. There’s no great way around the emissions of flying right now, and while I don’t think offsets solve every problem, they at can at least help here. Even more so, I want to make sure I’m going places mindfully, making the most of each visit, keeping the number of over-ocean flights small.

🗺 Emphasizing respect for locals. I think I’ve always tried to be mindful of the fact that travel is on other people’s home land, but the sense of entitlement around being able to go places I sometimes see makes me recoil- and I’m not necessarily immune to it. I want to make sure I always remember that going places is a privilege.