Lessons about speaking against injustice over the past six weeks

It’s been six-ish weeks since the protests began. Six-ish weeks since our country’s attention was grabbed by a series of police murders and demonstrations that followed. Six-ish weeks since many corporations, organizations, and people declared their plans to listen and learn about racism in America, then to make changes. Some actually followed through.

I too, wanted to intensify what I was doing to dismantle racism. I do believe that our individual battles take place in the circles where we have the most influence- whether that’s through position, relationship, or otherwise. I began thinking of what messages needed to be heard by faith communities, by Filipino-American communities, by the nonprofit world, etc. And I started writing and hitting publish.

Those posts turned into some meaty and meaningful conversations. And in turn, they taught me so much about standing up for others, speaking up, and how to do so strategically and sustainably.

Here are some of the biggest lessons I’ve learned recently:

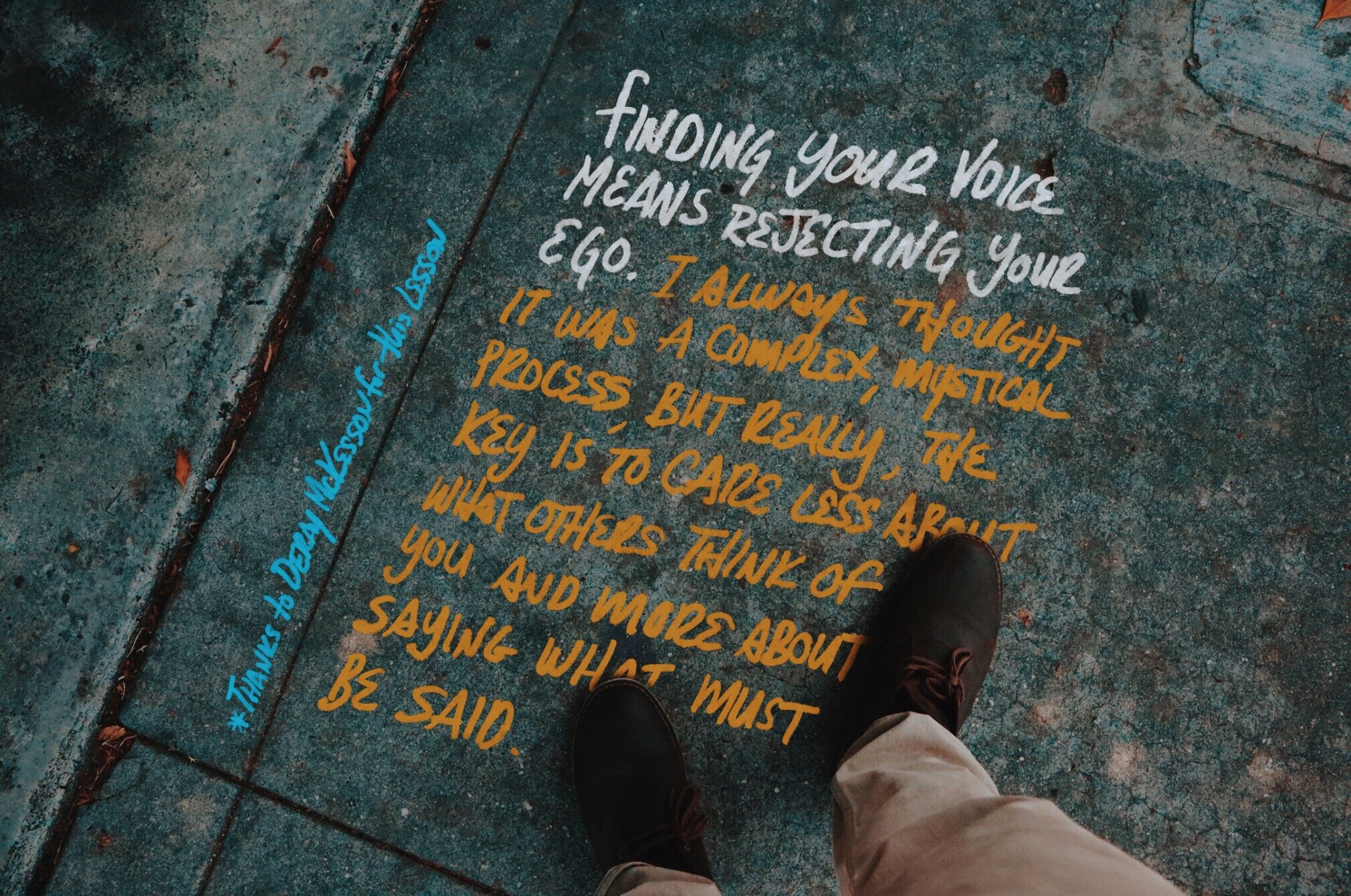

Finding your voice means rejecting your ego

Here’s what I mean by that:

A big part of any creative journey is learning how to “find your voice.” Once you know how to spread your message in a way that is distinctly yours, everything clicks. Of course, it’s easy to romanticize this idea without actually understanding what finding your voice looks like.

Finding your voice isn’t just about having your own distinct style. It’s about having an important message to say, and being willing to take risks in order to share that message.

And that risk-taking is calls for the rejection of your own ego.

This idea first came to me by way of Deray Mckesson, who once wrote “I found my voice when I lost my ego.”

And after the past six weeks, I relate to that.

A big reason why so many people remain silent during injustice is because of a fear around how they’ll be perceived by others. So many would rather not “rock the boat,” even if doing so means pretending the boat isn’t already in the process of capsizing. In order for us to move away from silence and towards action, we’ve got to lose our inhibitions around what-others-might-say in response.

Early on during the protests, country-folk singer Jason Isbell became very vocal about his support for Black Lives Matter. While anyone paying attention to his lyrics and music might not have been too surprised by that, those who simply took him as another voice from country radio stations were surprised and challenged. The warning “You’re gonna lose all your followers” came after him on Twitter.

“Maybe so,” he replied, “but I get to keep ALL of my SOUL.”

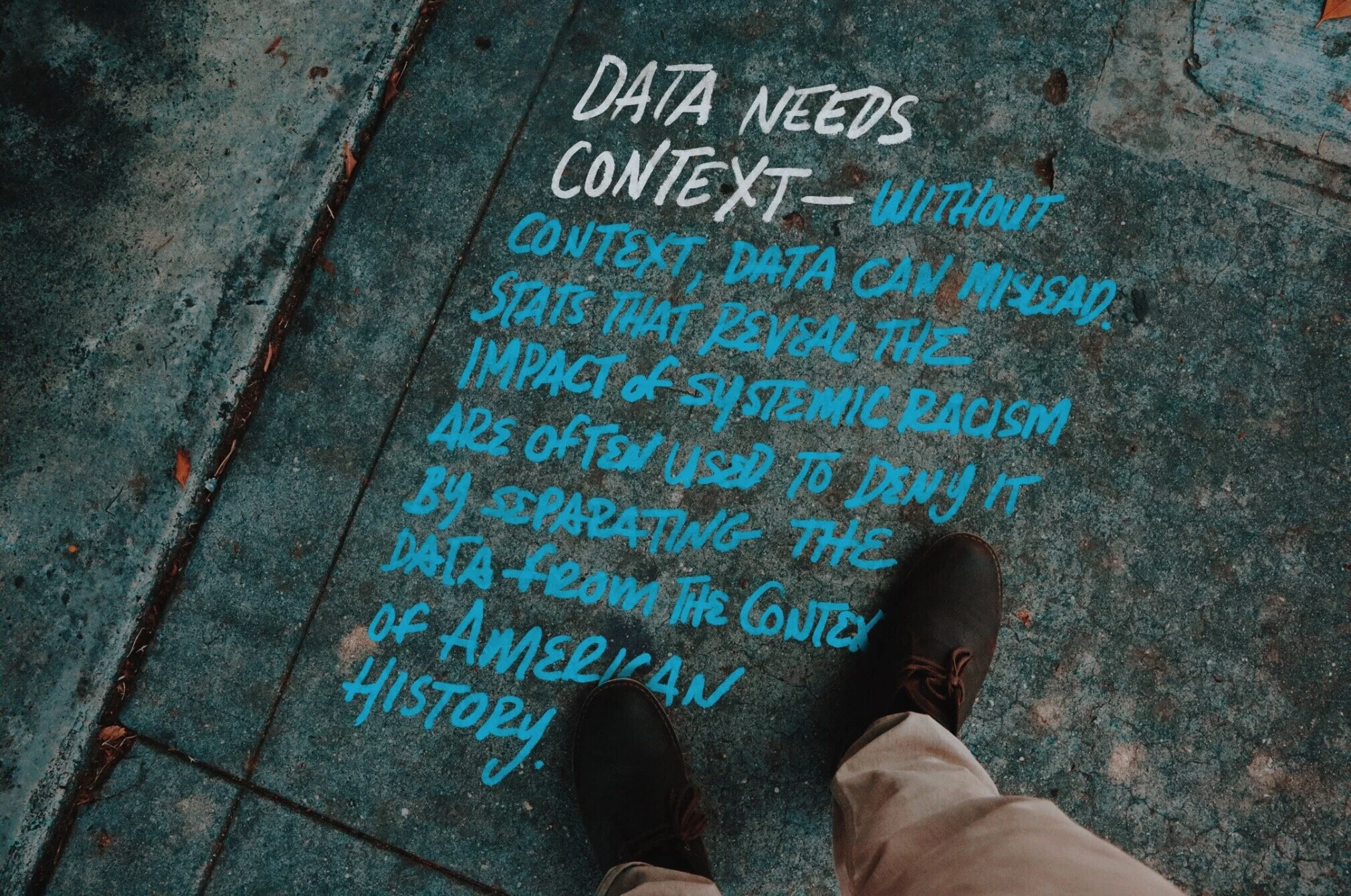

Data Needs Context

Here’s what I mean by that:

A phrase started going around social media the other week: Debate Club Racism.

Ogorchukwuu defines Debate Club Racism as when people use debate like tactics to rebut the lived experiences people have had with racism. She suggests using questions that probe as context as a way of moving past this common defense during important conversations about racism.

What informs your opinion? Who taught you what you know about racism? What do you lose by acknowledging racism?

In certain circles, it can be easy to think of data as objective. Numbers don’t lie, right? Well, in any scenario, there are actually infinite ways of measuring things numerically or statistically. We pick the set of data that is necessary to answer our questions, questions that are raised by context.

Here’s an example:

The United States has 4.4 percent of the world’s population. The United States also holds 22 percent of its prison population.

What’s the conclusion? Are Americans that much more sinister and criminal than any other country?

Context means we see a stat like that in the light of how prisons in the U.S. are for-profit businesses, incentivized to have a large population. It forces us to look at the origins of imprisonment as a way to continue to use people as property after slavery was abolished. The numbers don’t tell the story, but they verify it.

I like to think of data as a 2D snapshot of a 3D world. Photographs can verify our assumptions and offer us evidence. But, ultimately all photos are taken from a single angle, one that sometimes hides things and keeps other things out of frame. In some cases, it can even be used to create illusions.

Thats why context matters.

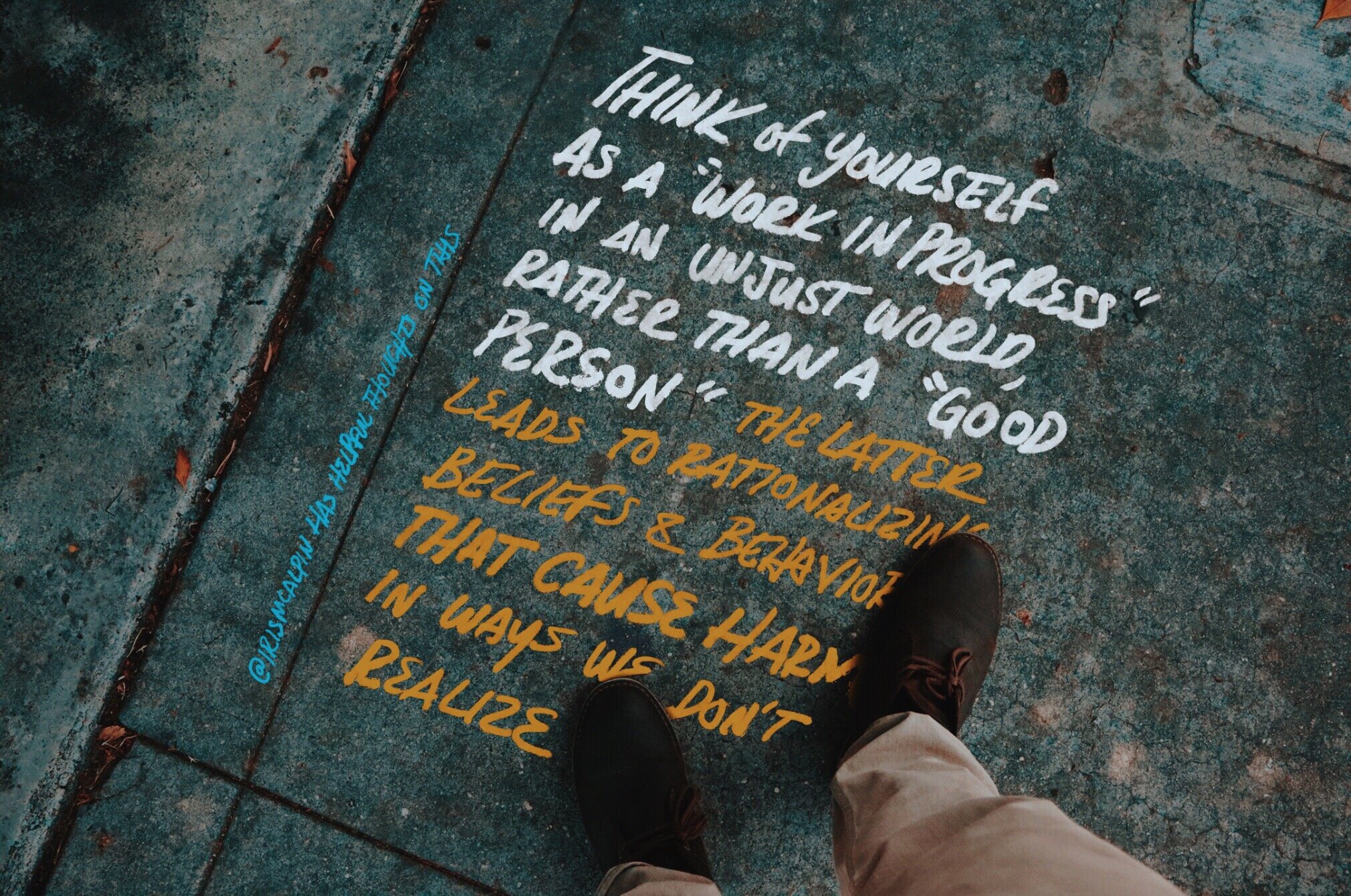

THINK OF YOURSELF AS A WORK IN PROGRESS

Iris M. Calpin has a great explanation of what I mean by this:

I am not a good person. I am a person who is equally capable of doing good and causing harm. Even with the best of intentions, my actions can have an unintended negative impact, and focusing on intention rather than impact is dangerous.

When our identity becomes wrapped up in being a “good” or “bad” person, we begin to see everything we do through that lens. We become masterful at explaining why what we did was “good” (or “bad”), regardless of impact. We shroud ourselves with our intentions, and the results can be quite devastating.

When I was in high school I picked up a book called The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang. It is probably the most impactful book I have ever read. It details how “good,” “normal,” everyday Japanese people participated in the brutal mass slaughter of Chinese in 1937-1938. It was painful to read, but it imprinted on me that human cruelty is not “out there” being committed by “monsters.” It is within us, right here, committed by human beings.

This is vitally important to recognize. When we externalize the issue, and reduce bad actors to “monsters” we let ourselves off the hook. We get to pretend that we’re good, and innocent. We get to ignore the ways we’re complicit in the perpetuation of harm.

With what’s happening right now, if you’re white, you’re complicit. I’m complicit. Racism isn’t out there, it’s in here. We’ve all internalized it. It’s woven into the fabric of our culture, and until we deeply and fully acknowledge our role, and take conscious action to remove it from our minds, bodies and hearts, it stays.

correct others and get used to being corrected

Here’s what I mean by that:

If you are doing the work, then you frequently use phrases like the following:

“That was a problematic statement, do you know why?”

“I’m sure you didn’t mean to come across this way, but when you said _____, it seemed like you were suggesting ______.”

“Let’s not talk about ______ that way.”

The specific words you use and the most ideal tone will vary by situation and your relationship with the person you’re talking to. But no matter what, it’s gotta happen.

I haven’t always done the best job of responding decisively and with clarity to problematic statements, but that’s one thing I’ve committed to much more firmly over the past six weeks.

Thanks to the timeliness of current events, lots of us are starting to think of prejudice as a virus. It’s a pretty helpful analogy. Keep going with it.

The virus spreads through words and ideas, and is often spread by people who are unaware or in denial of their condition. Without the proper treatment of being corrected, those ideas plant themselves more firmly in the person who said them, and are often absorbed by people listening. Often, they might be absorbed in a very subtle and subconscious way, but over time, this creates a norm where those ideas are allowed to persist without consequence.

Pointing out when somebody says something ignorant, hateful, or wrong can be like taking apart a virus before it can spread.

I know a lot of people bite their tongues because of not wanting to sound strict, coercive, prudish, or holier-than-thou. You don’t have to call people out in a strict, holier-than-thou way. But the very act of speaking up is itself an act of humility, because you’re putting your own comfort on the line.

Don’t fixate on tearing down opponents, but setting them free

Here’s what I mean by that:

It can be difficult to want to humanize somebody who refuses to humanize others. I also want to be clear that I’m not at all in favor of “giving equal attention to both sides.” In matters of antiracism, there’s one side I firmly want to be on.

But, when you’re talking to a family member who espouses racist views, sometimes it can be tempting to want to unload all your feelings and knowledge and on that person to forever silence them. More often than not, this is more cathartic than strategic, and it ends up serving your feelings more than it contributes to the ultimate goal.

Shifting a person’s viewpoint doesn’t happen quickly. In early conversations, being able to plant a few seeds of doubt (even if they aren’t acknowledged) is progress.

Popular media might have you believe that winning a debate looks like dropping enough truth bombs on to another person until they’ve been totally defeated. However, a defeated person usually retreats further into their own beliefs, making that approach frequently counterproductive.

The long, hard process of listening, asking clarifying questions, acknowledging any and all points of agreement, and repeating back the other person’s ideas with your own failure to understand how it makes sense are all more pragmatic approaches.

This isn’t to say there aren’t times we need to go hard against certain points. Those are there too, especially when others are involved in the conversation than the person you’re directly talking to. But always consider the probable effect of your approach.

What has always helped me keep patient has been to remind myself that the person I’m talking to was created for such intense good, and I’m in the process of helping set them free of ideas that hold them back from their truer purpose.

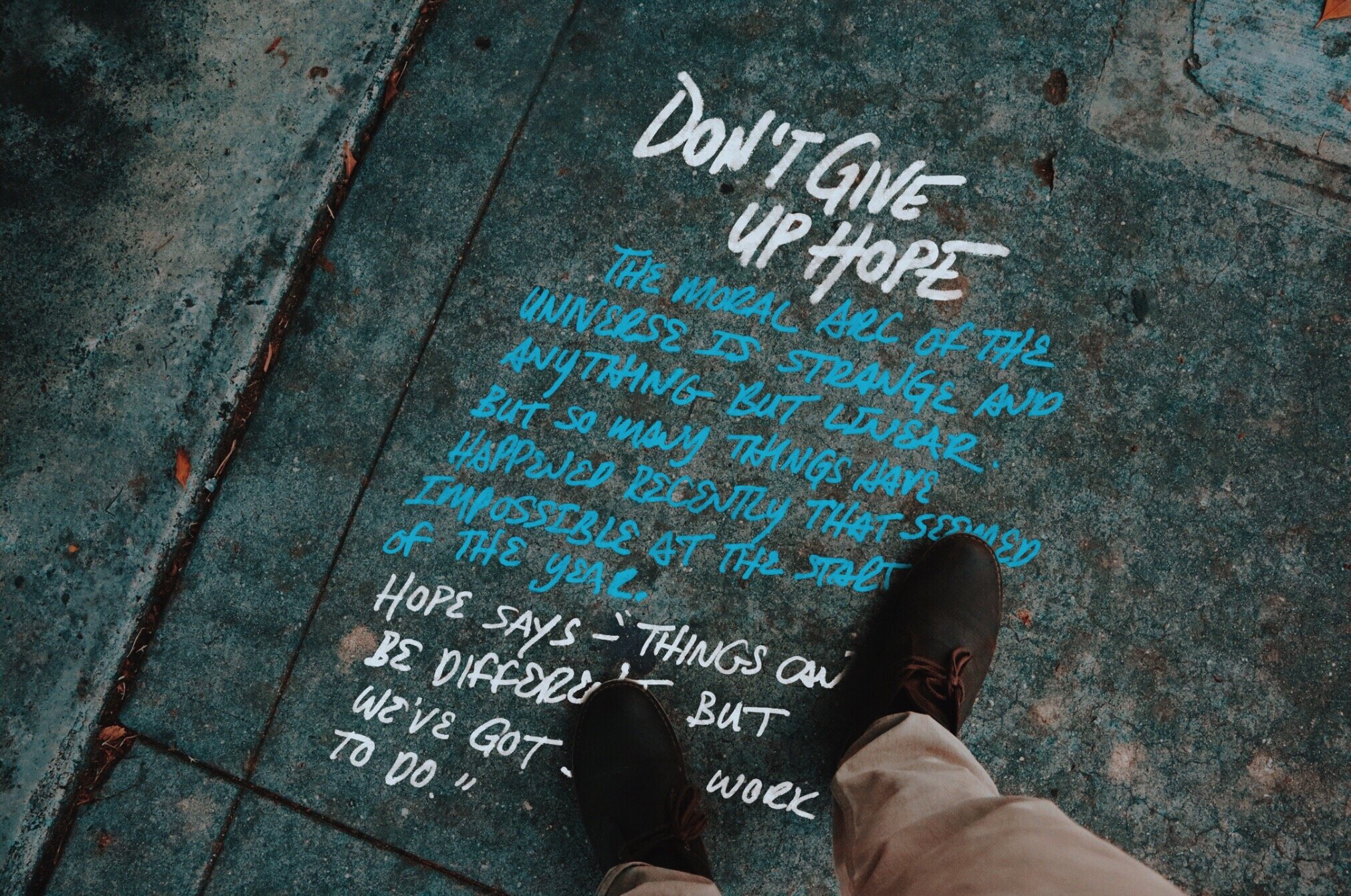

DON’T GIVE UP HOPE

Here’s what I mean by that:

My thoughts on this aren’t complicated. It’s easy to lose hope when it feels like a lot of people only cling so tightly to hateful and harmful beliefs and refuse to listen to anything else.

But the past several weeks have shown me a few things.

Sometimes, change can remain stalled for years, even decades, before suddenly the willpower to create change comes like a tidal wave.

When that wave of change comes, be ready for it. Be ready to make moves while the moment allows.

That wave of change often happens when the people who have been comfortable with taking a position of neutrality for years suddenly find their silence uncomfortable.

Things get to that point after years of steady work and effort by people during times when progress seems stalled.

Just remember all that the next time change feels impossible.