STORIES

photos

journal

A LAND OF STORIES

Bangladesh- you contain a world of stories!

It makes sense that a place known for being densely packed with people would also be packed with their stories.

So many people I encountered living truly challenging lives, jobs that are the hardest I’ve ever seen being performed right in front of me. At the same time, even the exhaustion couldn’t override the Bengali spirit.

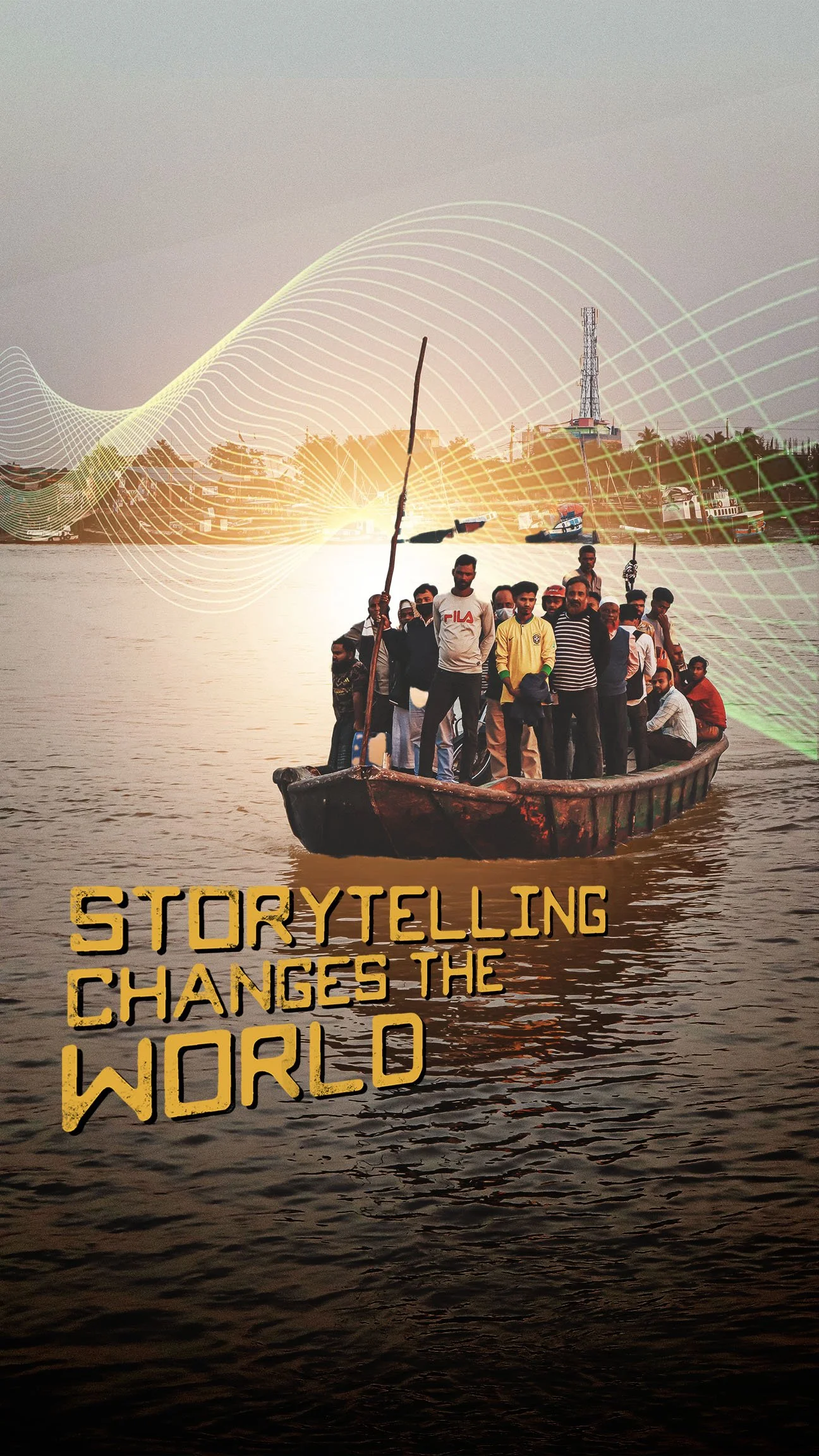

Resilience is a word that often gets misused. It’s admirable, but sometimes we let that warmth of admiration obscure our sense of urgency to remove the conditions that demand resilience from a population. Still, it’s impossible not to use the word when confronted with the hard, full-hearted stories up and down the Buriganga River.

SOMEONE ELSE’S ORDINARY

You go to a new place, a new environment, and every detail pretty much jumps out at you. The tone of the sky. The vehicles you don’t see anywhere else. The energy and pace of life. It stands out as otherworldly. Every new sensation is an invite to ask new questions, occasionally ones you ask out loud.

It’s different. But to everybody else out there, it’s normal.

If you were to approach even the most mundane task with fresh eyes, there’s nothing mundane about it. Take a toddler to a barbershop for the first time for a perfect example. We forget about this when we’re in one place for too long, kind of like how most people don’t recognize the smell of their own house as anything other than neutral.

I love being somewhere I’ve never been, at least partially because it makes me rethink my idea of ordinary. If all these details to me are a novelty, then that’s true in the reverse direction. My ordinary life, the parts I take for granted or think of as unamusing, would be mindblowing from another point of view.

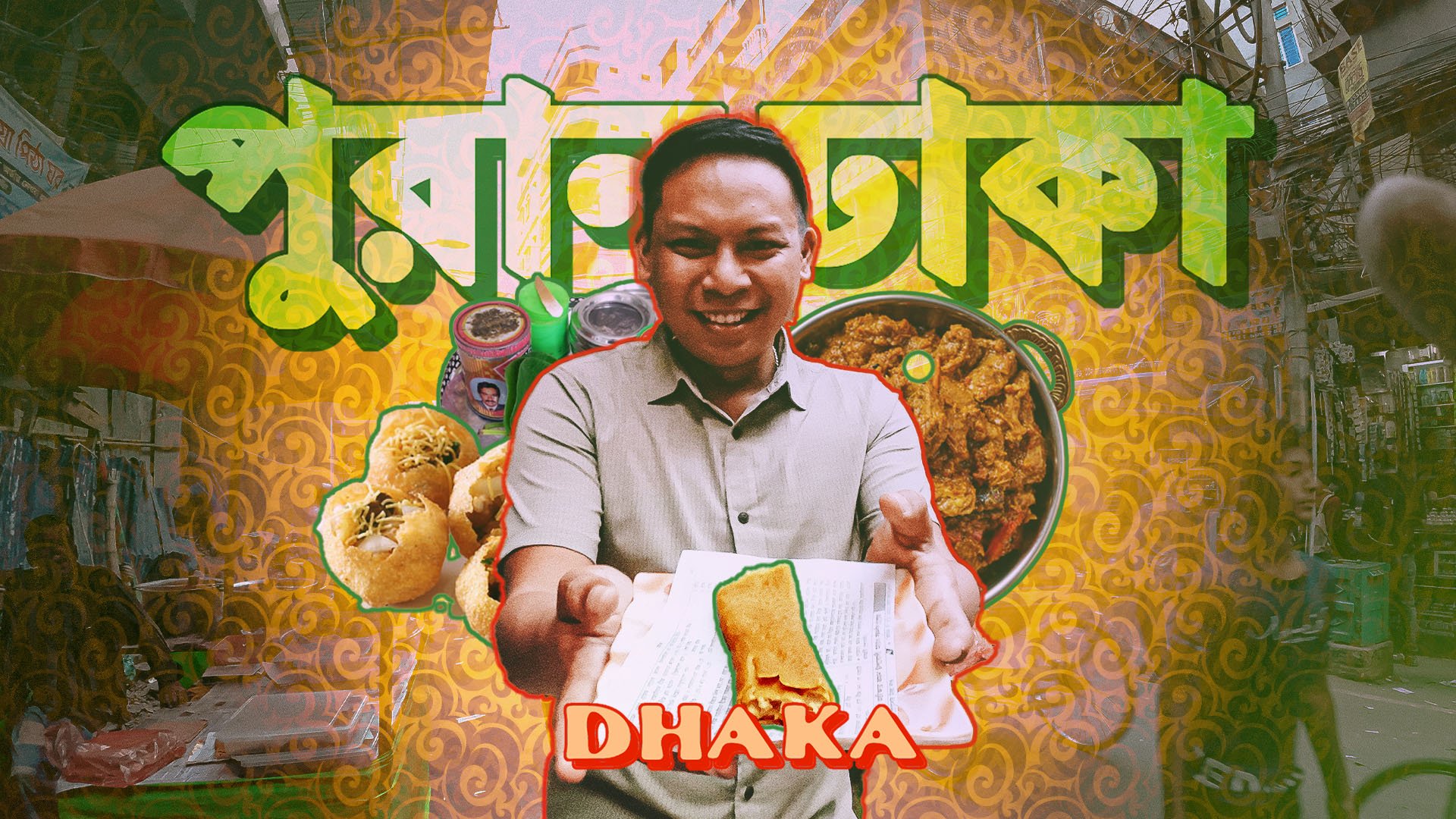

Betel Nut

Paan. Betel leaf.🍃Stuffed with candy, spices, chocolate syrup. Then lit on fire and shoved in your mouth.

Sounds good?

Apparently this snack is illegal! Or at least in a legal gray area.

I have a video dropping next week about the time I took a food tour of Old Dhaka. Really excited to put it out there so make sure you’re following along on the Tube and the newsletter.

Also, recognizing my room for growth here. If I’m gonna do this food and travel stuff on camera, I gotta go bigger with the reacts! 🫠 So stoic for having fire just put in my mouf.

RICKSHAW ROADRAGE

Heat make anyone else cranky?

I hate being too hot. And apparently so do a lot of people, as evidenced by the rickshaw roadrage I ran into on this street through Old Dhaka. South Asia gets some notoriously brutal temperatures. It was an efficient brawl, the two bike cab drivers hopped off for a 90 second fistfight before carrying on their way. Not to condone violence, but at least this approach was efficient, and way less destructive than whatever happened on Beef.

BRICKS & POLLUTION

I came to Bangladesh primarily wanting to talk to people engaged in solving its biggest problems. The most inescapable challenge, particularly in Dhaka, is air pollution. The city routinely ranks as the most polluted in the world.

Surely there was somebody with a plan. A strategy to change this.

I found out that the primary culprit for the pollution were Dhaka’s brick kilns- there were over a thousand of them around the city. At any given brick kiln, you could find hundreds of brick workers, people who took these difficult and dangerous jobs because their rural livelihoods were lost to climate change.

The irony was that Dhaka needed to produce so many bricks because it was growing quickly, but the reason it was growing so fast was because of all the climate migrants arriving to replace their farm income with jobs like these.

A solution to the pollution in Dhaka might not necessarily begin in Dhaka. Anything to lessen the threat of climate change curbs migration, the pressure on Dhaka, and the risk of people working under such harsh conditions.

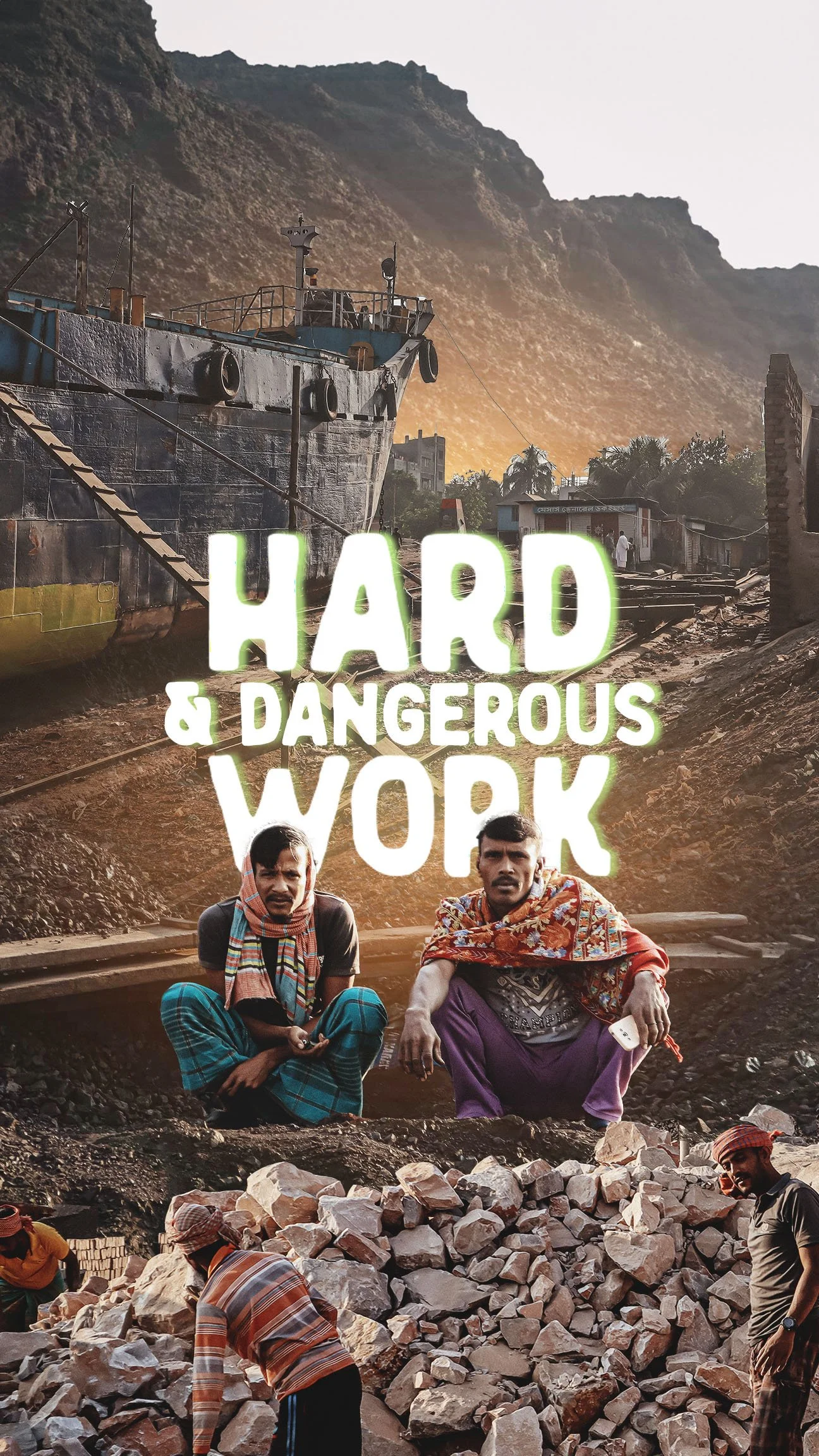

The Most Difficult Jobs

Bricklayers who worked fourteen hour shifts in the Bengali heat, inhaling the dust from their construction.

Shiploaders who carried two hundred loads of coal and other materials overhead across planks from cargo ships to shores, over and over.

Metalworkers in alleyways who worked without proper protective gear to take apart the scraps of old ships.

In one square mile of Dhaka I saw all of the most difficult, laborious, and underpaid jobs being worked by climate migrants. Obviously, they wound up in this position because of one unfair systemic problem stacked on top of another.

When you see the effects of hyper consumption and a climate crisis firsthand like that, it makes you wish a direct response was a little bit more within reach. But truly, the only sustainable solution was to go upstream. To look at the root causes, and work from there. In the meantime, the best immediate action someone could take was simply deciding to take a posture of listening to their stories and perspectives.

Climate Migration

Climate migration is a serious challenge. I’ve heard so many farmers talk about facing the difficult decision of having to leave their homes to provide for their families once the harvests came up short.

Of course, having to leave your family is always difficult, however it occurs. But it was in Bangladesh, I saw firsthand how challenging it is when people actually have to follow through on this difficult decision.

In Dhaka, I witnessed some of the most difficult and demanding jobs I’ve ever seen. I tried just walking across a plank to one of the coal ships and that was difficult enough. But the workers had to do that two hundred times each day carrying heavy coal-filled baskets over their heads. While I watched the welders and mechanics in the alleyway just behind the shipyard, I saw so many close-calls and nearly-missed accidents. I was told by many people that it wouldn’t be too surprising if I actually witnessed one. They happen frequently.

One of the first issues that made me really care about human rights were abusive labor situations. I heard stories of physical jobs, not too unlike these, in South Asia where severe abuses took place. It occurred to me that creating a healthy climate where people don’t have to leave their homes greatly reduces their vulnerability to ending up in this sort of situation.

INTO THE SUNDARBANS

After hearing so many stories from climate migrants, I knew I needed to leave Dhaka, to see the home villages so many of them referred to. Getting to see the Sundarbans mangrove forest close up. In real life. Bengal tiger territory!

I did not see a tiger… but that’s actually a good thing. The stories I heard of the tiger-and-human interactions were all pretty tragic. For both species.

I did see plenty of macaques, but those guys are jerks most of the time. Lots of white spotted deer, which are gorgeous. And then some crocodiles. I did not realize that a croc can live up to 70 years old until this visit, but that’s pretty cool.

The Eco-Village of Banojibi

My trip to the Sundarbans introduced me to BEDS, a nonprofit working in Southern Bangladesh. I had the opportunity to discover one of their big initiatives, an eco-village called Banojibi.

The people who live on Bangladesh’s coastline are extremely vulnerable to climate change. That became obvious just seeing how their farms and homes were situated.

Banojibi turned out to be a very holistic project. It was part training center, part regenerative farm, an energy hub, an ecotourism center, and more. This community was both equipping them with better environmental management techniques while improving their lives financially and via infrastructure.

Water Solutions

There’s a big irony when it comes to island nations like the Philippines or low-lying coastal countries like Bangladesh. Water should be abundant, but because of the really high salinity, drinking water can still be scarce. Extremely high saline concentrations also makes the water less suitable for farming, which is a problem that climate change intensifies.

I loved these Water ATMs I found in Bangladesh, installed by the organization BEDS. Eco-villages can manage their own water-treatment facilities by using local knowledge, the nature-based solutions of Pond-and-Sand Filters, and technologies like solar power and reverse osmosis.

The introduction of the ATM system has made these services more widely available, connecting about 12,000 people with clean water. Water-borne illnesses are no longer a concern, and local women have more opportunities without having to spend hours collecting water.

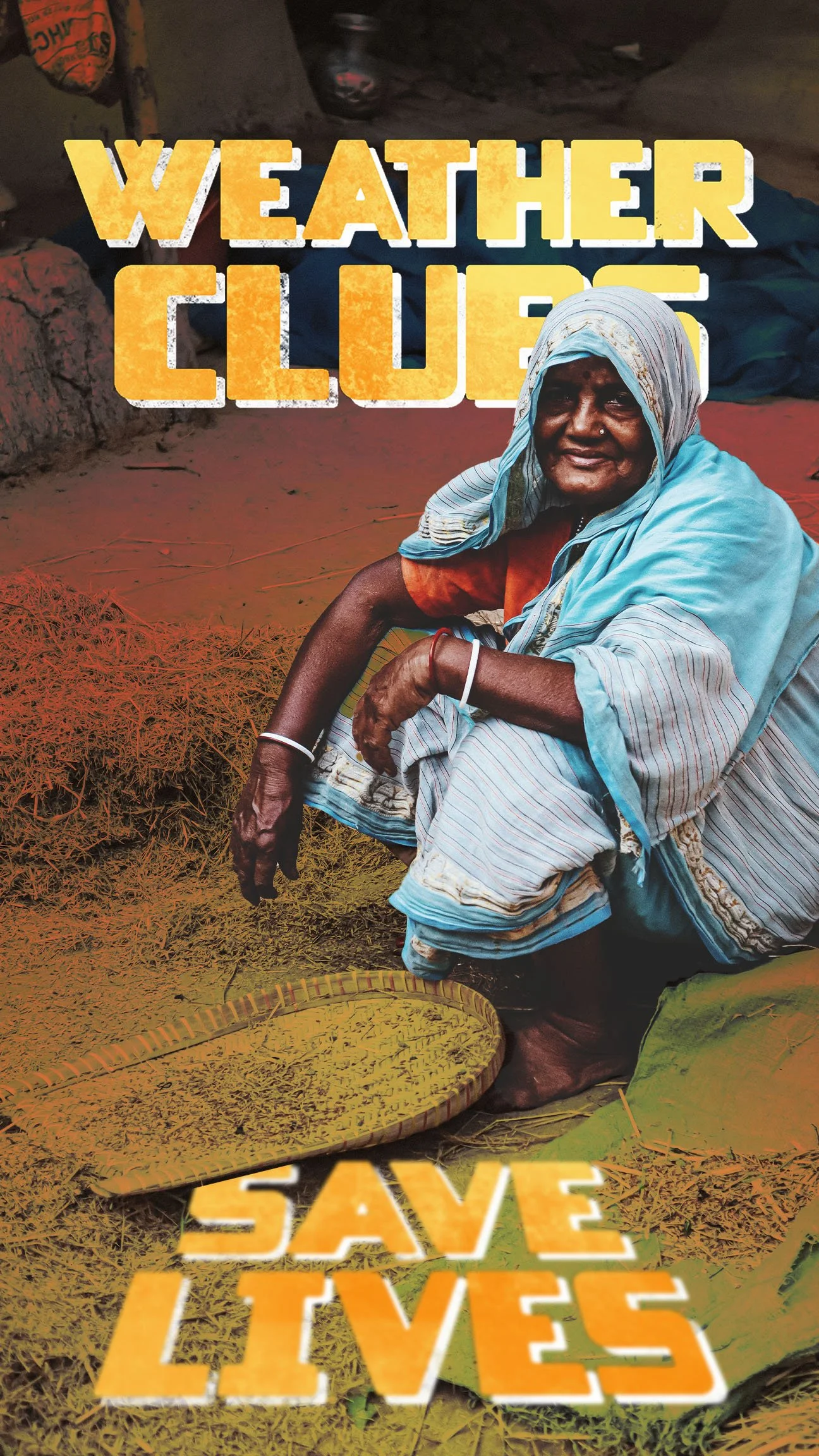

The Mothers of Mongla

In my head, I kept thinking of this trio of women I interviewed in the Sundarbans as the ‘Mothers of Mongla.’ While their kids played some customized mashup of football and cricket in the background, they told me that they had joined a weather club that gave them the chance to prepare their neighbors from pending cyclones.

Interestingly, they referred to the place where they lived as a mother. “In the Sundarbans, we feel like we are under the mother’s care. This is my birthplace, I will always feel emotionally connected. As I said, we are under the mother’s care in this area. We are proud to live in this beautiful place.”

Turns out, when you realize your dependence on the land around you, you respect it!

I UNDERESTIMATED BANGLADESH

Confession: Before visiting Bangladesh, my interest was mild at best. When the things you hear about the most are crowds and smog, those aren’t exactly high selling points, and even people from there made it seem underwhelming.

But if you have the right people to show you around to the right places, there is an absolute wealth of stories and things to explore. The people are warm, welcoming, conservative, and absolutely determined to push forward in order to make a better life for the next generation. Problem-solving is an ubiquitous trait, and seeing that applied to major threats like climate vulnerability was eye opening.

Bangladesh is a country that has a lot to teach its visitors, if given a fair chance.

sketchbook

The Bricklayer

Last month, Cyclone Mocha made landfall on Myanmar and Bangladesh, claiming lives and threatening to displace hundreds of thousands of people.

It made me think of men and women I met on the Bangladeshi coast, not far from that area, last winter.

They told me about cyclone seasons. Bangladesh really is one of the most climate vulnerable countries on earth and it intensifies the impact of these cyclones.

I’ve heard so much about the climate vulnerability of Bangladesh. But you know what I hadn’t heard about as much? All the people- local people- who were doing something about it. Mothers, farmers, bricklayers, technicians. Yet another reminder to never see people as totally helpless.

Look for the helpers… but don’t forget to start looking among the locals.